Data Science for Experimental Design – loopy stuff

Posted on 18 March 2019

Data Science for Experimental Design – loopy stuff

Adam, the first ever robot scientist.

Adam, the first ever robot scientist.By Alex Morley, Institute Fellow & Mozilla Fellow.

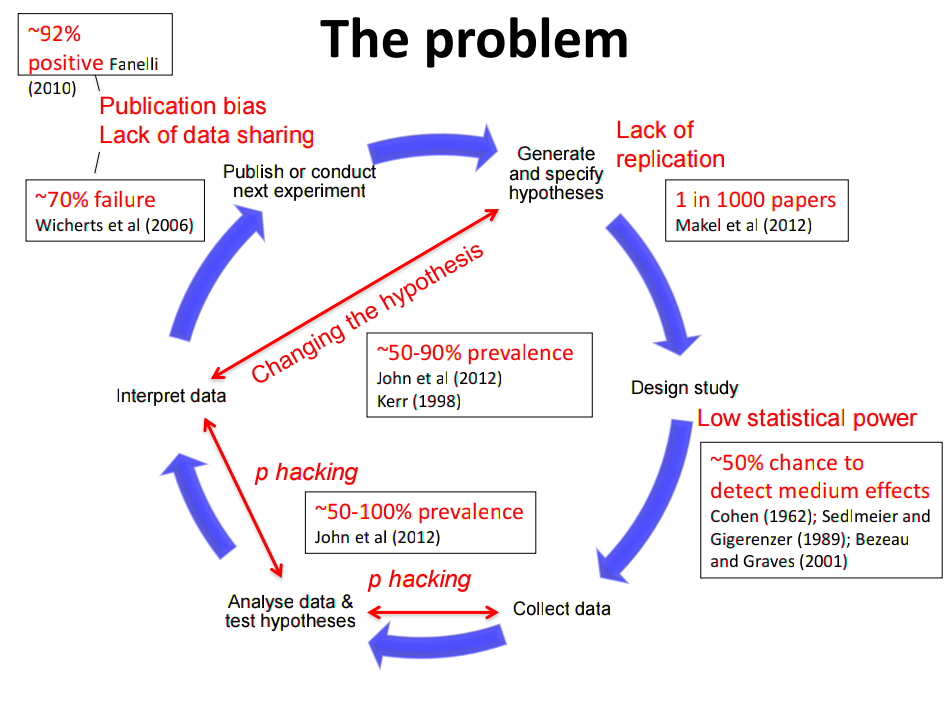

It’s not a new concept. But when people talk to me about improving the scientific process it really resonates with me when they talk about feedback loops. This framework is broad enough to encompass most ways in which we can think about improving science, but also makes explicit what actions need to be taken, and where bottlenecks are likely to arise. Here are a few examples of how people have used these cycles to make/explain progress/problems in scientific processes.

Examples of feedback looks in the scientific process

So I was super excited when the first thing I saw at the Data Science for Experimental Design workshop, held at The Alan Turing Institute, was Daphne explaining how we were going to cover each part of the cycle. Unfortunately I haven’t been able to get a copy of that slide yet, but from the other images you might be able to imagine how it might look.

Pre-registration prevents hacking of the scientific feedback loop.

Pre-registration prevents hacking of the scientific feedback loop.Chris Chambers. Find out more here.

Loop Number 1 - Optimising Experimental Design

The first two talks of the day discussed optimisation algorithms for experimental design. Here we focus on how we can implement closed loop systems that enable us to run experiments that make optimal uses of the resources available, both in terms of time and cost. We were told how finding solutions to these systems can be hugely computationally expensive, and discussed some potential avenues to find shortcuts that are just as good. It’s worth noting that this type of work involves collaborating with statitians and data scientists in the planning stage of an experiment. All too often we reach out for advice try to solve our inference problems after the data is collected, by which time it may already be too late.

Loop Number 2 - Automating the discovery loop

Then we moved on to the next level of abstraction, how much of the scientific process can we automate. Ross King told us about Adam, a machine he claims is the first ever robot scientist. In Richard’s view, one of the key steps to sharing science in a reliable way is to use formal, logical languages, rather than natural ones like english or mandarin. By programming a machine using these languages, Richard’s team could extract all the steps from a high-level goal, e.g. “What does this yeast gene do?”, down each layer of abstraction to the observations made on the sensors of the machine.

In the last session before lunch, Dr Vishal Sanchania from Synthace, described Antha, a software platform that has a somewhat smaller remit that Richards robot scientists, but works out of the box with a wide range of hardware, and an thoughtful user-interface. This level of abstraction seems appealing, but many members of the audience were concerned about the lack of clarity in the availability of the source code, or whether there would be an open API that would freely allow third party customisation.

Loop Number 3 - Sharing, Evaluating, and Re-Using

After the break we had the reproducibility crew and Dr Rachael Ainsworth and Dr Sebastien Besson. Dr Besson spoke about his lab’s project The Image Data Resource and Omero. One of the key points in the scientific feedback loop is other researchers being able to explore the data that lead the original authors to make the concolusiont that they did. These databases allow anyone to explore all different types of image data and metadata in their web based browsers.

Dr Ainsworth then took us on a whirlwind tour of open science. From why you should do it, why your worst collaborator is yourself in 6 months time (hint: your past self doesn’t reply to emails), and some great re-mix and re-use of materials from colleagues open science talks.

Structural and Cultural Barriers to Implementing Optimal Feedback Loops

“we need to make sure we consider the effects of the changes we seek to drive in as many different contexts as possible [or …] we risk not only being ineffective but actively contributing to existing societal inequalities”

To close off the day three scientists with sociological backgrounds lead discussion groups about cultural and contextual considerations for moving forwards with Data Science for Experimental Design. For me two themes resonated loud and often in these sessions, in terms of what we as scientists should be doing to be effective, 1) we need to actively engage those with expertise in driving institutional change to help us in our efforts 2) we need to make sure we consider the effects of the changes we seek to drive in as many different contexts as possible. The latter point is especially important, what works to increase accessibility to science in one context may not work in another, and without taking these considerations into account we risk not only being ineffective but actively contributing to existing societal inequalities. These considerations might be technical e.g. considering low-bandwidth internet users when you share data, or not, e.g. using graphics to aid those who find large sections of text difficult to understand. This can often be extra work but remember also that the wider the audience you consider the wider the audience you have the potential to reach.