Continuous Integration: Fail Fast and Fail First

Posted on 27 February 2020

Continuous Integration: Fail Fast and Fail First

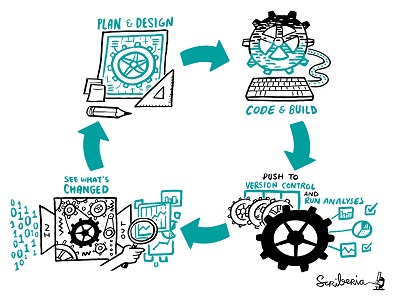

Image by Scriberia for The Turing Way community

Image by Scriberia for The Turing Way communityused under a CC-BY licence

By Sarah Gibson, Research Software Engineer at The Alan Turing Institute and Software Sustainability Institute Fellow, and Graham Lee, Research Software Engineer at the University of Oxford and Head Labrarian at Labrary

Sarah and Graham have different career backgrounds - Sarah having come through academia whereas Graham earned his stripes in industry. However in their current roles, they often find themselves using the same tools, for example Continuous Integration. They have written this blog post to identify how academia and industry may use Continuous Integration in different ways, and what they might learn from one another.

What is Continuous Integration and why do we use it?

In Continuous Integration (CI) and Continuous Deployment (CD), the key concept is “continuous”. That is where it departs from what software engineering teams were doing before: rather than eventually integrating, at the end of developing a feature, we do it continuously, as we’re working. Instead of eventually deploying, when we’ve got a collection of features built and bugs fixed, we do it continuously.

The tools we use for these activities help us integrate and deploy continuously. Our pipelines give code authors and reviewers information about the quality of their submission, and its readiness to go into our products.

These tools also hinder continuous integration and deployment. How? Generating that information takes time, so development is slowed down waiting for the build job, test run, or other pipeline task to complete.

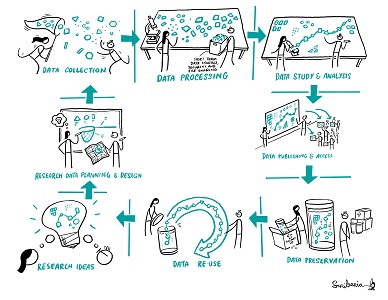

Image by Scriberia for The Turing Way community

Image by Scriberia for The Turing Way communityused under a CC-BY licence

Long-running pipelines

People very rarely set out to create very long pipelines, they happen by accumulation. We set out to improve our test coverage, and the time spent running tests increases. With compiled languages like C++ or Java, our efficient, best-practice build system becomes slower as our projects gain features and complexity.

Sometimes, we find new tools that can benefit our workflow, and add them to the pipeline to provide automatic adoption. Code formatting tools, static analysis and advanced error detection systems, automatic documentation generators: they can all add value to our work by improving our code, but they all take time to run and that time comes at a price.

A long-running pipeline interrupts our mental flow. The longer it takes your tools to give you feedback, the more likely you are to go and read Slack, or check Twitter, or get up and make a coffee, while you’re waiting. Any of these activities disrupts your mental context and it’ll take time and effort to get back into doing your work.

Ideally - but probably impossibly - it’d be great to have a visual indication in your IDE, updating live, that everything is OK, or that there’s an issue. Imagine if as you typed, your Jupyter notebook ran your tests and showed a big tick or cross in the corner. As you edit your Pydoc comments, the API documentation on your Github page is changing to reflect your typing. As soon as you press save, a new version of your library appears on PyPI.

Unfortunately each of these activities actually takes time, so we need to make some choices. We want to find the sweet spot between gaining confidence in the software we’re writing, and keeping our pace and focus up.

Prioritise failure

If the goal of a CI or CD pipeline is to determine that a code change is a good candidate for integration or deployment, then it can finish as soon as it has determined that a change is not a candidate. If a test fails, no amount of further inspection or analysis is going to make that test pass - the code needs changing.

This is “failing fast” - giving up as soon as you have indication that there’s a problem. Most workflow tools, including Github actions and Jenkins, will stop as soon as a step in the workflow fails. For example, they won’t run the unit tests if there’s an error in the build.

You can speed things up even further by stopping the test step as soon as any test fails, instead of gathering and reporting all test results. As an example, the popular jest test runner for Javascript has a --bail <n> option, which exits after n test failures are detected. In the popular Python testing module pytest, the equivalent is --maxfail=n.

Making this change makes it faster to discover that something is wrong, at a cost of not finding out how much is wrong. In a way, this doesn’t really matter. Contributors should be encouraged to satisfy themselves of the quality of their work before submitting a pull request, so that the pipeline is only a backstop and not the first place they find out about problems.

Fail first

Another technique to speed up pipelines is to put the steps that cover the most likely or impactful failures first. If developers don’t tend to use a feature of your software, and therefore break it frequently without noticing, run the tests for that feature early in the pipeline. If a failure in a component would have a huge impact on users’ work, make sure to test that early.

This borrows from the electrical engineering concept of a “smoke test”. A quick test for problems in electrical equipment is to plug it in and check whether it starts smoking. If there’s no smoke, it doesn’t tell you that there’s nothing wrong, but does suggest you can move on to more detailed inspection. If the magic smoke escapes, there’s no need to do any further testing.

You can arrange to fail first without needing any test-ordering facility in your test runner. Create separate steps in the pipeline for the smoke tests and the wider test suite. If you can tell your test runner what directory or folder to find tests in, then you can organise your test files into separate suites.

Run the smoke tests first, and fail the pipeline if any of them doesn’t pass.

Come back later

Maybe there’s information you need, but you don’t need it now. One of us (Graham) worked in the Developer Efficiency group at Facebook, where hundreds of commits per day were being made by developers all over the world. If the continuous integration pipeline took too long on a patch, then the code would have changed out from under the patch author - Facebook use trunk-based development so everybody is committing to master - and they’d have to fix it to resubmit. Hardly continuous integration!

The pipeline that ran on commit only performed smoke tests and some basic analysis, and automatically merged the commit if these tests passed. Separately, a more complete (and longer-running) set of tests ran on a schedule.

If tests failed in the scheduled suite, how did we know what to do? The CI system automatically bisected the failure, using the previous run’s commit as the last known-good commit and its own as the first known-bad commit. Sometimes the failure couldn’t be isolated to a single commit because they were introduced by infrastructure problems, but often bisecting would identify a code change that caused the failure. When it does, an issue can be raised and assigned to the commit author to fix the problem.

What implications does this have for Continuous Analysis?

As the discussion around reproducibility in academia develops, many researchers are turning to software engineering practices, such as CI, to verify their results are reproducible as they develop their analysis code. The idea being that a Continuous Analysis (CA) pipeline will alert a researcher to a commit which changes the output of their code. They can then investigate whether this change is due to coding practices or a fundamental change in their model, and the implications of that new model.

But here we run into the same problem. As the models gain complexity, they become longer to run (sometimes taking months!) and perhaps require High Performance Computing (HPC) resources that are not available on most CI/CD platforms. So how can we break this down?

We should say that it is possible to run a job launched by CI on a HPC system, however it is not straightforward and often involves using secret variables.

More often than not, it’s the model generation or simulation scripts that take the most time and power to run, whereas the analysis scripts that produce the results for the paper are much smaller and can be run locally. So we might save model and/or data artefacts in our repository with our code and perform CA on this last step. In the meantime, the larger simulation code runs on a schedule on HPC facilities to produce model/data artefacts.

In an ideal world, the simulation code would be written such that it has a test case which can be run to test functionality and usage. This is often a smaller simulation that sacrifices resolution in order to test functionality within a reasonable timeframe.

There are some other factors to consider when testing code on HPC systems - such as billing, user logins, scheduling and queuing - which we won’t cover here.

Conclusion

Building an effective continuous integration, delivery or analysis pipeline is a balancing act between getting useful information about potential changes, and allowing the developers to maintain focus and work at a good pace. Being selective and risk-focused in the design of your pipeline makes sure your team gets important information as responsively as possible.

Sarah and Graham would like to acknowledge the very helpful comments from Tim Powell concerning testing HPC code.