Maintainers III: labour

Posted on 15 November 2019

Maintainers III: labour

Photo by Cesar Carlevarino Aragon on Unsplash

Photo by Cesar Carlevarino Aragon on UnsplashBy Dr Laura James, Software Sustainability Institute Fellow

This blog post was first published on Dr Laura James's own blog on 27 October 2019.

Labour was a theme cutting across sessions at Maintainers III.

There was one specific session exploring it, which turned out to be quite data-driven (but also US-specific). Data about labour is often missing, for various reasons. Half the workers in the US are paid by the hour, so their overall wage is unknown and with unpredictable work schedules statistics struggle to paint a realistic picture. Many people have two or three or more jobs; perhaps 40% have some sort of 'side hustle'. Some forms of intangible labour, such as that of graduate students in universities, are hard to track (that's on top of the unpaid labour in care, in the home and so on).

This is perhaps unsurprising given people are generally happy not to know about the poverty and precarity of others.

Quite a few sessions discussed unions and labour organising, including mention of the Tech Worker Coalition as well as more traditional unionisation. In the US, collective bargaining was developed in a way which perhaps was problematic for maintenance, as employers determine what labour looks like.

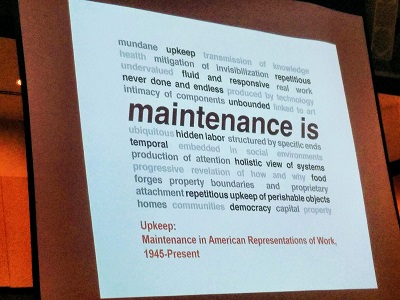

There are so many forms of maintenance labour. A lightning talk on maintenance in American representations of work since 1945 by Brandon Benevento was a whistle-stop tour of maintenance labour, including this summary:

Slide from Brandon Benevento

Slide from Brandon Benevento

Brandon talked about maintenance which aims to keep up health, wealth, discipline, empire - not all things we might wish to maintain, now.

Maintenance is an active discipline - even to maintain a status quo. Think of the red queen of Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass, who must run to stay in the same place. In fiction we also encounter vivid depictions of what happens when things are not maintained, with gothic tales of dilapidated castles. The execution of minute tasks is critical in maintenance, and linked to larger outcomes.

Like other speakers, Brandon discussed gender and maintenance labour, and he also touched on maintenance as a Marxist project, concerned not just with exploitation, but with ideologies such as efficiency, and the experience and quality of work.

Maintenance can be the worst work. Maintenance can be the best work. It always sets the individual into a larger, systemic world or role. We are all maintainers, but different amounts. Some people maintain more. Some people maintain more for the benefit of others.

He concluded that maintenance is a uniquely valuable concept.

I didn't go to any of the sessions in the Information Maintenance track, because there were so many fascinating things to choose between, and Information felt less relevant to me right now. Nonetheless I spoke to many participants during the conference who were mostly in this track - and their experiences and interests resonated with me from my time working in technology to support teaching and research, at CARET in the period just before we merged into the University Library. The self-described 'radical librarians' were a familiar type :)

Through these conversations, and the report back on day three, I still got a sense of the questions being explored by the librarians, archivists, curators, technologists and others of the information track. There were definite overlaps in areas with the software track which looked primarily at open source software maintenance - particularly in consideration of the individual as a maintainer.

What does it mean to maintain information? What does a disciplinary identity mean, and is it helpful, or not helpful? Care and concern for a discipline, either one's profession or as a maintainer, must be balanced with care for yourself. This came up in the context of how to raise the profile and status of maintenance in these fields. Information maintainer roles - those that are paid, at least - often require an advanced degree, and therefore (in the US at least) debt, or lost income; class needs to be recognised here.

A wider question was the possibility of a widespread reorientation of information maintenance, when thinking about climate and social justice. How can lower status maintainers not be complicit in injustice? Is caring for yourself, and your profession, as much as you can sufficient? There was a sense of a drive for change here, for greater action, but it was recognised that despite the collective power of workers, organisational change is hard and slow. Will it really happen? How do we make that change?

This, then, was the overarching question I took from the Information maintenance track: if this part of the world should be different, how do today's maintainers go about changing it? If we wish to move to a maintenance economy, as Shannon Mattern and Indy Johar called for at the 2019 Festival of Maintenance, how do we start?

On an individual level, perhaps it means saying no (even to tasks you have been doing so far), letting things break or die. Or perhaps it means stopping masking what is already broken. But how do we work out what we might let go, and who pays the price when these things are no longer maintained? An example from nursing was that you might do all you could for direct patient care, but allow other things to break, such as IT systems. There is also fear that, if you stop maintaining some things, your area could be cut, as in so many information maintenance areas there is not enough resource to care for and steward everything. Is doing a few things well, or many things badly, the best defence for a maintainer? These are questions of power - who says no, and what is the impact of that?

Stopping maintaining things, or doing a bad job, is a cultural and mindset challenge for a professional service role. Are there other contexts where service people have stepped up to demand respect, which info maintainers could learn from?

On the other hand, there is richness in the brokenness, sometimes, and how things break, which we should remember.

Perhaps collective action has more potential. Could a union offer protection to those who might be saying no? Could a guild of some sort demand better work, good work? What can we learn from the organisations which are sustaining, but which are staffed by 'shifts' of people who fight hard for a while for change and then leave when burned out? We heard about French police and firefighters, who cannot strike as withdrawal of labour would endanger people. Instead, when there is a strike issue, they continue to work but wear sashes or T shirts describing their concerns and explaining they are still offering service whilst striking. This gets a lot more popular support for their causes.

How can you tell the difference between being complicit vs actively contributing to an unjust and problematic system? Where do activities such as taking notes in a meeting sit? There were few good answers here, but it was suggested that one might take an inventory of all the things you maintain, and examine them to see which are furthering justice.

Overall, these discussions brought together big social change challenges, with the challenges of day to day life as a maintainer of information, with modest pay and status, often in under-funded institutions with many stakeholders. It was encouraging, at the end of the report back session on the final day, to hear from Stewart Brand of the Long Now Foundation. He reflected that the activities being undertaken by Maintainers now - events, consciousness raising, art - are the ways powerful movements start, and we can expect leaders to arise from this community, labour to organise, and change to come in time. It's a case of working out which tactics to use when, and trying things out.

A very different take on maintenance and labour came from Melissa Gregg, who spoke about maintaining composure as a freelancer. This form of life is more common now, as work and life blur for many people, and a mix of mobile office, flexible work, and multiple roles which are always with you. For many freelancers, this means constant productivity pressure, chronic overload and notifications and beeps, and numerous to-do lists and time management tools to try to manage it all. (Melissa is the author of "Work's Intimacy", from 2011, and the more recent "Counterproductive - time management in the knowledge economy".) What even is work, in a 'constant-on' society? People don't count email as work, which might be problematic as it could easily be half of your job.

Melissa surveyed students, entrepreneurs and small businesses, creative workers such as live streamers, and freelancers, across the US, China and Sweden, and examined how these diverse groups used technology.

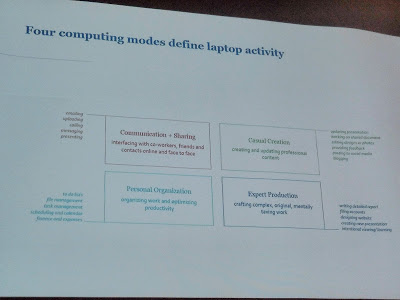

She identified four distinct modes of laptop use, differentiating communication ("the work of getting the work done", like email), casual creation, personal organisation (maintaining files, claiming expenses, scheduling), and expert production.

Melissa Gregg's slide on laptop activity

Melissa Gregg's slide on laptop activityI found the difference between casual creation and expert production especially interesting. Casual creation includes things like updating a presentation, giving feedback, social media - it seems like an ancillary activity but is actually a growth category, increasingly required of professionals. There are many new digital tools to help here. Expert production is the thing that you actually think a creative/ freelancer/ entrepreneur actually does - writing a detailed report, designing a website or other new thing, or in the case of a student, intentionally learning. It's complex, original and mentally taxing work, and technology tools are designed for this. Users want to spend more time on this, but actually don't spend much time on it.

The blurry line between work and social is highlighted by apps such as Slack, born from the realisation that people like to chat, even when they are not face to face, and not in the same team. It's software created for phatic reasons, not the instrumental reasons of traditional corporate life.

Melissa talked through some examples from her research. Casper, the freelance designer with three laptops - one Mac, one Windows, one for a customer's system. The student who grew up using GSuite, but is now forced to use the university's Canvas system. Almost all her work is in the cloud, and done collaboratively. Even though she's using a laptop, a seemingly personal device, almost all her performance is visible to her peers, and most of what she writes is consumed by others on screen. She's dependent on Canvas to manage notifications coming in all the time - tasks due and so on - and suffers from anxiety around her peers seeing all her work in progress.

People who started using computers before mobile phones expect larger screens; they feel better if they can see, say, a whole weekly calendar, and not just the next few hours on a phone screen. Screen size matters, so people can see where they fit, in these coercive and social new work norms.

Older people, who have had a 'personal computer' for some time, have always found filing information on their PC a burden and it continues as such. Today's freelancers have remote cloud storage, and juggle bookmarks and elaborate setups of tabs and history. Browser tabs are used heavily, especially for communication, and personal organisation. People may have over a hundred tabs open, and have apps dedicated to organising them. There's a fear of turning off the laptop, because of lost 'history' and 'context' - things that are hard to express, but matter a lot. "Saving" is now "syncing" and local storage seems unnecessary - it's a very different way of thinking about computing.

The consumer cloud offerings of, say, Google, are essential for freelancers. SMEs go for freemium solutions, as they scale up, paying to get stuff done.

People are overwhelmed by the volume of information, and we are now moving to a new era in terms of storage, where our metaphors are changing.

People in knowledge professions have these old ways of thinking, and are now using a laptop as a sort of temporary vessel only - it's a confusing and stressful evolution. (Given the upcoming era of machine learning and less predictable computing, I can only imagine this will get much worse before it gets better.)

Next generation knowledge workers face different challenges to those of recent decades. For instance, when digital infrastructures such as Slack go down, what happens? How are workers affected and how do they develop strategies to handle this? Who - or rather, what institutions - do you depend on for your infrastructure?

There's been a rise in coworking spaces and 'office as a service,' where Wifi is the most critical infrastructure. One provider of coworking said they have three different wifi backups so it never goes down, it's the only thing they invest in. Today's freelancers and entrepreneurs can't afford a five year lease, but they can pay for coworking, to get a network (like a previous generation might have got an MBA), and for proximity to people and transport hubs.

However, for many of these workers there's no reliable support or care for their device or connectivity or data. There is no one to go to when things go wrong. You have to maintain all these systems yourself.

Many PC companies, such as Intel where Melissa works, still assume you get a corporate computer from your employer, but that's not the reality for many workers (even those apparently at corporates, who may well be freelance). She's trying to show them that this isn't the case any more, and that the way devices are provisioned and maintained needs to change to reflect the modern work reality.

There are also problems for executives. Now that we fetishise productivity, people who once had someone to delegate logistics and admin to are finding they don't have anyone to do that for them any more. Productivity apps are repair for the trauma of losing your secretary! This may also be one of the reasons people think email isn't real work - because correspondance used to be the domain of low status secretaries.

A questioner noted that the personal digital archiving literature often shows contempt for people and their helplessness in the face of information management. Are the only two ways forward either better systems that might take away the burden, or 'everyone needs an archivist?' How can we address the concerns of freelancers in their precarious work, whilst avoiding reintroducing a feminised labour of archiving?

(Melissa closed by noting the habit of checking email on the weekend, and how there is something about today's middle class professional style or personal satisfaction that cannot sustain, as it ignores a century of self help knowhow.)

Many speakers discussed gender and maintenance labour. Communication and social maintenance have often been gendered, as have archiving and record keeping.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles wrote the Manifesto for Maintenance Art in 1969, calling for a readdressing of the status of maintenance labour in the private, domestic space, and in public.

Maintenance is a drag, it takes all the fucking time. -- UkelesMuch of the Manifesto points to gender issues.

The desire to be productive is also gendered. Time management techniques have a history in domestic science and home economics, where the first versions of time management practice and instruction arose. Women were the first managers of households.

Another lightning talk, this time by Yuan Yi, explored labour history in cotton factories in China, contrasting the skills of allegedly unskilled female cotton workers with those of male mechanics. The factories arrived in areas where textile labour was established, mostly handicraft based and female. When industrial looms were set up in factories, the celebrated aspect of those looms were the innovations, the machinery and the male mechanics who kept it running. (This reflects the literature on industrialisation which considered "tinkering" as a form of innovation, rather than maintenance.) When there were problems with the machines and fibres broke, women were employed to tie and manage the threads, using the skills they had from the more traditional manufacture to maintain the factory processes. Handicraft skills were critical for the success of the factories, but not recognised.